Lee Miller: From Vogue Muse to War’s Unflinching Eye

- Ian Miller

- 10 minutes ago

- 5 min read

The astonishing life of a woman who reinvented herself again and again — and captured history as no one else could. 🌍📷

Cover Image

Caption: Lee Miller, Vogue cover model, New York, 1927.Photograph by Edward Steichen — image courtesy Lee Miller Archives.

Lee Miller’s life reads like a novel — rich with beauty, surrealism, glamour, danger, and unflinching truth. Born Elizabeth Lee Miller in 1907 in Poughkeepsie, New York, she began life in a comfortable household, yet her destiny would pull her far from that quiet Hudson Valley town into the heart of fashion, art, and ultimately, global conflict. Today, we remember her not merely as a model; nor only as a Surrealist artist; nor strictly as a war correspondent — but as a visionary who transformed photography itself.

The Early Light: Hollywood Looks, Paris Dreams

Image: Lee Miller posing for Vogue, 1927

At age 19, blue‑eyed and striking, Lee Miller wandered Manhattan with an ambitious restlessness. Fate intervened dramatically: she stepped off a curb into traffic, and the man who pulled her to safety was none other than Condé Montrose Nast, publishing magnate of Vogue. Captivated, Nast put her on the March 1927 cover of Vogue — launching her modelling career in grand style.

Her face soon appeared in glossy pages, photographed by fashion masters: Edward Steichen, Arnold Genthe, Nickolas Muray. But Lee was never content to remain still in front of the camera. She hungered to be the one holding the lens.

Image: Fashion editorial portrait of Miller, late 1920s

She briefly became the first model featured in a menstrual product campaign — a Kotex advertisement that scandalised polite society in 1928 — yet it also underscored something essential about Miller: she pushed against conventions, even those that sought to tame her image.

Behind the Lens: Surrealist Paris

Image: Lee with Man Ray, Paris, 1929

Caption: Student, muse, lover — and soon, a photographic force.

In 1929, restless with success, Miller left New York for Paris. There she sought out a figure who would change her world — the Surrealist photographer Man Ray. Initially insisting he did not take students, Ray relented when Lee declared, “I’m your new student.” What began as an apprenticeship blossomed into romance, collaboration, and creative symbiosis.

Together they experimented with solarisation, a technique that inverted tones and evoked dreamlike textures. Whether by accident — including a famous story involving a startled mouse in the darkroom — or by design, the result became one of the era’s definitive visual signatures.

Image: Solarized portrait by Miller (c. 1930)

Caption: Light and shadow’s dance — Miller’s exploration of solarisation.

Yet their bond was not merely technical. In Paris salons and cafés, Miller befriended the avant‑garde: Picasso, Cocteau, Paul Éluard, Meret Oppenheim. Her presence elicited both myth and mythmaking. In Jean Cocteau’s film The Blood of a Poet, she played a statue — a fitting metaphor for a woman whose body and gaze would be both object and agent in the creative revolution of her generation.

Queen of Her Own Frame: New York and Europe

Image: Self‑portrait by Lee Miller, early 1930s

Caption: The artist becomes the subject — Miller’s self‑portrait.

By the early 1930s, Miller had returned to New York where she opened her own studio with her brother. Her theatrical training in lighting and her uncanny sense of composition made her work stand out. She photographed celebrities, created fashion spreads, and balanced commercial success with artistic ambition.

Her career then took a cosmopolitan turn. In 1934, she married Egyptian railroad magnate Aziz Eloui Bey and moved to Cairo. There, she photographed pyramids and desert landscapes — becoming as much an explorer as an artist. But the desert soon gave way to surer loves: Europe and the Surrealists.

Love, War, and the Camera that Knows Everything

Image: Miller and Roland Penrose in the 1930s

Caption: Partnership and art — life with Roland Penrose.

Back in Europe, Miller met British Surrealist Roland Penrose in 1937. Their personal and artistic partnership defined a new chapter. They mingled with Picasso again, traveled, and bonded over the European avant‑garde.

Yet as war raged across the continent, Miller’s eye shifted from abstraction to atrocity.

During the London Blitz of 1940, she photographed a city under siege. These images — later published as Grim Glory: Pictures of Britain Under Fire — balanced stark documentary power with her Surrealist instinct for the uncanny.

By 1943, Miller became an accredited war correspondent for Vogue, a path few women trod. With Life magazine photographer David E. Scherman, she followed the U.S. 83rd Infantry Division through Normandy and beyond, photographing front lines, bombed towns, soldiers, and civilians in shock and resilience.

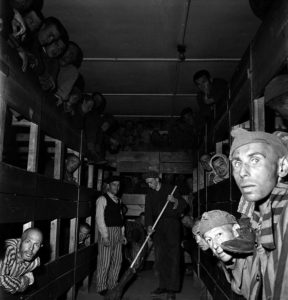

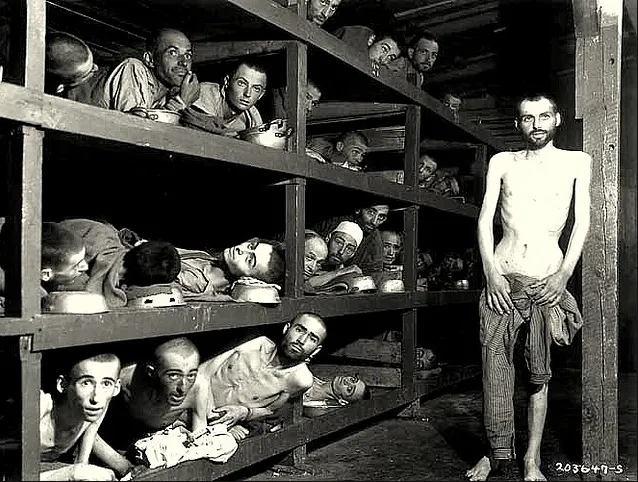

Her lens did not flinch. In Rennes, Saint‑Malo, and ultimately in Germany, she captured images of devastation and survival — photographs that would become some of the first visual testimony from liberated Nazi camps.

The Bathtub Photograph: An Icon of War

Image: Lee Miller in Hitler’s bathtub, Munich, 1945

Caption: Defiance and irony — Miller in Adolf Hitler’s bathtub, April 30, 1945.

One of the most striking photographs of World War II is not a battlefield. It is a woman in a bathroom.

On April 30, 1945 — the day Adolf Hitler died — Miller and Scherman found themselves in Hitler’s Munich apartment. With the ruins of war still smoldering outside, Miller climbed into the dictator’s bathtub to wash off the mud of Dachau — and Scherman photographed the moment.

The image captures contradiction and catharsis: a survivor bathing in the tub of tyranny, boots still muddy on the bathmat. It has become an emblem of Miller’s fierce independence, her unorthodox brilliance, and her refusal to romanticise violence even as she documented it.

Legacy in Print: Publishing & Post‑War Life

After the war, Miller continued her art, but the world was forever altered. Some of her most powerful images were seen in British Vogue and other periodicals, giving readers in peacetime glimpses of what they had lived through. Her photographs were more than documentation; they were emotional truth, often edged with the surreal sensibilities of her earlier years.

However, the cost of witnessing horror was steep. Like many wartime journalists, she struggled with her experiences — turning inward, drinking, and at times withdrawing from the public eye. Only through the efforts of her son, Antony Penrose, did her archives receive renewed attention, revealing a body of work spanning fashion, fine art, sociology, and history.

Why Lee Miller Matters Today

In the 21st century, Lee Miller’s legacy resonates on multiple fronts:

Woman in a man’s world: She broke barriers in journalism and art when women were routinely excluded from both.

Artistic hybridity: Her work absorbed Surrealism, commercial fashion, and hard‑edged documentary into a unique visual language.

Historical witness: Her war photography stands with the great reportage of the age, reminding us of the human face of conflict.

Cultural inspiration: From exhibitions at Tate Britain and major retrospectives to the recent biopic Lee starring Kate Winslet, her life continues to captivate audiences.

Conclusion: The Photographer Who Became Her Own Story

Lee Miller’s journey was not linear. It bent with the tides of history, moved through glamour and brutality, and ultimately defined a new genre of visual storytelling. She was a model who held her own in the harshest studios of war and art — a woman whose life was as vivid and complex as any photograph she ever took.

Her images remain haunting, brilliant, and deeply human — echoing a truth Miller once embodied: that reality itself, in all its beauty and terror, can be framed and understood through a courageous eye.

📸✨ Lee Miller lived many lives — but she captured one truth: the world is worth seeing, no matter how hard the gaze.

Comments